I’ve never been to the Galápagos islands. Tourist guidebooks describe them as a beautiful tropical paradise, and some travelers speak of them as a Garden of Eden.

But in 1835, when the young Charles Darwin visited the islands, he saw them very differently. In stark contrast to the lush, beautiful landscapes and colorful animals that Darwin saw in parts of South America and the tropics, the isolated islands were foreboding.

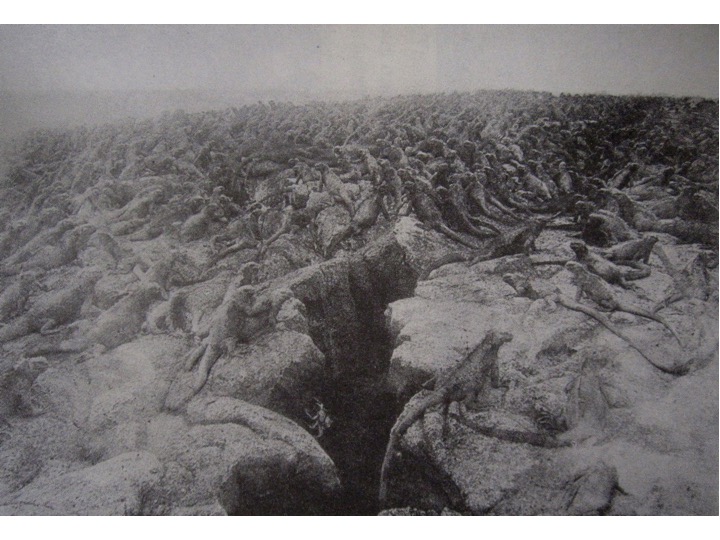

The Galápagos seemed dark and bleak: towering volcanoes, hot and extremely arid, lacking vegetation, and inhabited by very ugly creatures. As the H.M.S. Beagle sailed toward the islands, Captain Robert FitzRoy wrote that the jagged black rocks, crowded with huge, hideous iguanas and swarms of red crabs, reminded him of the legendary capital of hell: Pandemonium.

Back then, the Galápagos were not an ideal tourist destination. Instead, the islands were a place for exiles, mostly disgruntled “people of color” who had been banished from Ecuador for political crimes.

There were abundant strange reptiles instead of mammals, including large, sluggish crested iguanas, which they called “imps of darkness” and thousands of giant, deaf tortoises. To the twenty-six year old Darwin, they seemed like primitive creatures that had survived the Biblical flood.

And Galápagos animals were incredibly tame. Hunters did not need to shoot birds, they could just hit them. Darwin used the muzzle of his rifle to push a large hawk off a tree branch. The landscapes were haunting, with petrified convulsions of black lava and craters: “nothing can be imagined more rough & horrid,” he wrote. The leafless, stunted plants smelled foul. “The country was compared to what we might imagine the cultivated parts of the Infernal regions to be.”

Erie and spellbinding, Englishmen called them “The Enchanted Islands.” Those haunting islands inspired some myths and for some time I’ve been researching the evolution of myths in science.

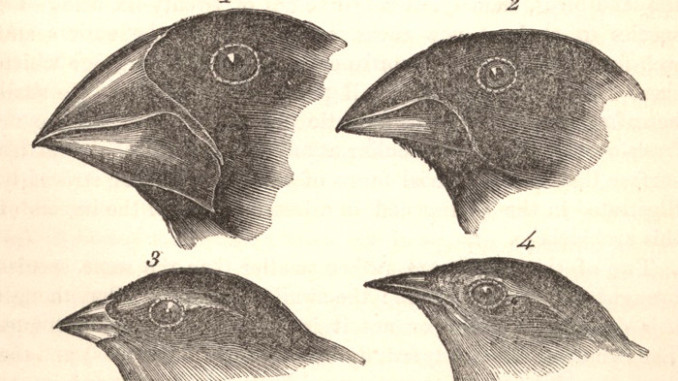

Years ago, I used to teach my students the famous story that finches on the Galápagos islands inspired Darwin to develop his theory of evolution. In my new book, Science Secrets, I summarize that old tale as follows:

While visiting the Galápagos islands, Charles Darwin noticed that various species of finches had beaks of different shapes and sizes. Observing their eating habits, he noticed that the shapes of their beaks corresponded to their diets. He also noticed that some species were distinct to some islands. Hence he inferred that the various species were related: they were descended from common ancestors that had populated the islands and had adapted variously to the distinct island conditions. Species evolved.

In 1982, however, Frank J. Sulloway of Harvard University argued that this story is false. He was right: Darwin barely observed the eating habits of finches, he did not correlate their beaks to their diets, and he didn’t know whether any finch species was unique to any island. He did not even label where he picked up each specimen of Galápagos finches.

The myth arose because in a book of 1845, Darwin mentioned that seeing the various finches in the archipelago “one might really fancy” that one original ancestral species had changed and diversified into several. But that was just a speculation; he had already believed in evolution for years, for other reasons. Actually, his knowledge about Galápagos finches was so inconclusive that he did not even mention them as evidence for evolution in the several editions of his famous Origin of Species. Instead, he gave hundreds of other arguments.

Since finches did not convince Darwin of evolution, it should not be surprising that they don’t convince many people nowadays either. I have never heard of a creationist who became convinced that animals actually evolve in light of anything about Galápagos finches. Nevertheless, the myth worked. It gave the illusion of understanding: a story of origins that seemed to convey how Darwin came up with a great idea, an illustration to put into schoolbooks.

Having confirmed that this story was fiction, I then had the question: what early findings, by Darwin himself, better show that evolution really happened? If we’re going to debunk “a likely story,” a tall tale, we should well put something in its place. Can we find a true story that works as well as a myth?

One alternative is to consider different birds. When Darwin left the Galápagos he struggled to organize the hundreds of specimens he had collected. He had labeled mockingbirds, at least, marking the places where he caught each specimen. And he was “astonished” that the Galápagos mockingbirds from Charles Island, Albemarle Island, and from Chatham Island were all different species. It seemed to make no sense because he saw these islands as nearly identical, and the current theory of species claimed that animals had been created to match their environments. Why would identical islands have different species?

Likewise, he remembered that some people in the Galápagos had said that they could tell from which island a particular tortoise originated just by looking at the shape of its shell. At that moment, still on board the H.M.S. Beagle in the Pacific Ocean, Darwin wrote in his notes that such remarks “undermine the Stability of species,” and should therefore be examined.

However, he could not examine the facts about tortoises, because he only took a couple of small specimens, as pets, and their shells showed no distinction. Captain FitzRoy had captured large tortoises, but as food. He and Darwin and the crew ate them all and they threw the shells overboard. They ate the evidence, as Sulloway remarked.

Anyhow, the claims by some men of the Galápagos were exaggerated, as actually the tortoises were hardly distinct to each island: instead there were gradations of shells, from saddle shaped to dome shaped. When zoos returned fifty tortoises to the Galápagos in the 1970s, to breed them with locals, specialists failed to identify the likely origin of any but one tortoise.

As for mockingbirds, Darwin did discuss them in Origin of Species. But he only mentioned them briefly, as an example of species endemic to certain islands. He then argued that “we need not greatly marvel” that some species had not spread to nearby islands, and he just did not refer to mockingbirds as strong evidence for evolution. So still, the question is: what good evidence did Darwin find for evolution in “the Enchanted Islands”?

Strangely, Dawin observed that some kinds of animals were missing on the Galápagos. In particular, there were no frogs, toads, or newts at all; what we now call amphibians, none. Darwin wondered, why not? Some of the humid island environments were well suited for them. There were so many different kinds of reptiles and birds, so why no frogs?

He found also that there were no frogs either in the Canary Islands, none at the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), none at St. Jago in the Cape de Verde, none at St. Helena.

In sum, Darwin found that the only kinds of animals on oceanic islands were those that could get there by natural means, from nearby continents. Birds, bats, reptile eggs and even mice on large rafts of floating vegetation from South America. Frogs could not reach the Galápagos alive, because they would get wet with saltwater, which kills them.

The evidence suggested that, like the people on the Galápagos, all the animals on the islands were actually colonists, or descended from colonists. The animals on the Galápagos were strikingly similar to those in South America, but different in some ways. But once we agree that the ancestors of the island animals all arrived from the continent, then we have to explain: why are they so distinct? So, to replace the old myth about finches, we now have the elements to tell a better story:

Halfway around the world, the young traveler Charles Darwin arrived at foreboding towering volcanoes, the “Enchanted Islands.” Their dark jagged terrain held swarms of hideous reptiles, “imps of darkness,” and tame birds. Yet Darwin found no frogs or toads on the islands. He found only the kinds of animals that could cross the salty waters from the continent. All resembled American species, but oddly distinct. He later concluded that such island species descended from colonists, but somehow evolved.

Compare this story to the old one. This story is just as short as the tale about finches, just as appropriate for a science textbook. But it’s better, I think, because it involves mythic imagery that is actually true.

For more on science myths, see:

Alberto A. Martinez, Science Secrets: The Truth About Darwin’s Finches, Einstein’s Wife, and Other Myths (2011). This book discusses more than thirty myths in fourteen chapters, all based on meticulous use of primary sources and new translations to carefully separate documentary facts from fiction in famous stories. These include Newton’s apple, Franklin’s kite, Galileo and the Leaning Tower of Pisa, alchemy, eugenics, and more, including also recurring questions such as: Did Albert Einstein really believe in God? Science Secrets shows how famous scientists, writers, and expert historians are all prone to misrepresenting the past because of the powerful urge to read between the lines and to portray conjectures as findings.

Leave a Reply